The Solomon Islands are known for their rich cultural and linguistic diversity. With over 120 vernacular languages, this Pacific nation is a fascinating example of how multiple tongues coexist. English serves as the official language, but it’s spoken fluently by only a small percentage of the population.

Instead, an English-based Creole called Pijin is the lingua franca, connecting people across the islands. This unique blend of languages reflects the nation’s history and cultural influences. Whether you’re exploring Honiara or the rural areas, you’ll likely hear Pijin in everyday conversations.

Understanding the language dynamics here offers insight into the region’s identity. From government communications to local interactions, the interplay between English and Pijin shapes daily life. Dive deeper to discover how these languages influence culture and community in the Solomon Islands.

Overview of Language Diversity in the Solomon Islands

Nestled in the Pacific, this archipelago boasts a linguistic tapestry as diverse as its islands. With over 120 distinct dialects, the region is a living example of how culture and history shape communication. The interplay of Austronesian and Papuan roots has created a unique blend of tongues, each telling a story of the past.

Historical Evolution of Linguistic Varieties

The language spoken here has evolved over centuries, influenced by colonization and indigenous traditions. Austronesian languages dominate, making up about 70% of the total. Papuan languages, native to the region, add another layer of complexity. Smaller language families, like Polynesian and Micronesian, also contribute to this rich mix.

Colonial history played a significant role in shaping the linguistic landscape. English, introduced during British rule, remains the official language but is less commonly used in daily life. Instead, Pijin, an English-based Creole, serves as a bridge between communities.

Cultural Significance of Multilingualism

Multilingualism is more than just a way to communicate here—it’s a cornerstone of culture. Communities often speak multiple dialects, reflecting their heritage and identity. For example, Kwara’ae and ‘Are’are are widely spoken, connecting people to their roots.

This linguistic diversity also highlights the importance of preserving endangered languages. Many traditional dialects are at risk of disappearing, taking with them a piece of the archipelago’s rich heritage. Efforts to document and revive these languages are crucial for maintaining cultural continuity.

Government Recognition and Official Language

The government here has a unique approach to language policy. English is the official language, used in legal documents, government proceedings, and media. Despite this, only 1-2% of the population speaks it fluently. This creates an interesting dynamic where the official language is not the most commonly spoken.

English in Official Contexts and Media

In official settings, English dominates. Government communications, legal frameworks, and educational materials are primarily in English. Media outlets also use it, especially in formal broadcasts and publications. However, informal media often switches to Pijin, reflecting the linguistic preferences of the general population.

Impact on Education and Public Life

The educational system emphasizes bilingualism, teaching both English and local languages. This approach aims to balance global connectivity with cultural preservation. Yet, challenges remain. Many students struggle with English proficiency, which can limit their opportunities in higher education and professional fields.

In public life, the contrast between the official language and everyday communication is stark. While English is used in formal settings, Pijin is the go-to language for most person-to-person interactions. This duality reflects the country’s complex linguistic identity.

| Aspect | English | Pijin |

|---|---|---|

| Usage in Government | Primary | Rare |

| Usage in Media | Formal | Informal |

| Usage in Education | Core Subject | Supplementary |

| Fluency Among Population | 1-2% | Over 90% |

This linguistic landscape highlights the government’s efforts to maintain a balance between tradition and modernity. While English connects the country to the global stage, Pijin ensures that the local culture remains vibrant and accessible to all.

Lingua Franca: The Role of Pijin in Daily Life

In the heart of the Pacific, Pijin stands as the glue that binds diverse communities together. This creole language, rooted in English but uniquely local, serves as the lingua franca across the region. It bridges gaps between speakers of over 60 indigenous languages, making it an essential part of daily life.

Pijin as a Bridge Language in the Islands

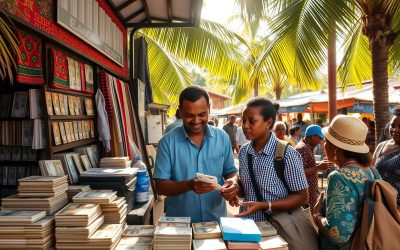

Pijin evolved from a trade jargon in the 1840s and stabilized by the 1920s. Today, it’s the preferred language for everyday communication, even though English remains the official language. In markets, schools, and homes, Pijin connects people from different linguistic backgrounds, fostering unity in this culturally rich area.

For example, in Honiara, children often learn Pijin before attending school, speaking it fluently by age three. This early adoption highlights its role as a bridge language, easing interactions in diverse parts of the region. Parents may prefer their children to learn English, but Pijin’s momentum among peers ensures its widespread use.

Media also reflects this preference. While parliamentary debates are broadcast in English, most programs by the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation use Pijin. This contrast between formal and informal communication underscores its practical importance.

| Context | Language Used |

|---|---|

| Daily Conversations | Pijin |

| Media (Informal) | Pijin |

| Media (Formal) | English |

| Education | English (Primary), Pijin (Supplementary) |

Pijin’s phonetic writing system and local expressions reflect the lived experiences of its speakers. Phrases like “Hemi Simoka Bilong Iumi” (this smoke is us) show its cultural depth. This blend of practicality and tradition makes Pijin an integral part of life in this region.

Regional Language Variations and Indigenous Tongues

Across this Pacific nation, language diversity paints a vivid picture of cultural heritage. With over 80 indigenous languages, the region showcases a rich tapestry of dialects and traditions. Each island and community contributes to this linguistic mosaic, reflecting unique histories and customs.

Languages by Island and Regional Group

Languages here are grouped by island and regional ties. For example, Gela is spoken by around 15,000 people, while Kwaio has about 5,000 speakers. These dialects often align with specific cultural practices, creating a strong sense of identity within each group.

In Polynesian languages, certain dialects like Sikaiana and Tikopia are spoken in outlier regions, adding to the linguistic richness. This distribution highlights how geography shapes language families and their evolution.

Endangered and Extinct Languages in the Archipelago

Many indigenous languages face extinction due to declining speaker numbers. Efforts to preserve these dialects are crucial for maintaining cultural continuity. For instance, languages like Rennellese are at risk, with fewer young people learning them.

In Papua New Guinea, similar challenges exist, with 839 languages at risk. This shared struggle underscores the importance of documenting and revitalizing endangered tongues.

Unique Dialects and Local Customs

Dialects here often reflect local customs and traditions. For example, the use of Pijin in daily life connects diverse communities while preserving indigenous expressions. This blend of practicality and tradition shapes the region’s linguistic identity.

Research on Pijin’s role highlights its significance in shaping cultural dynamics, especially in urban areas. These dialects are more than just communication tools—they are windows into the region’s soul.

Solomon Islands: Official and widely spoken languages

With over 60 distinct tongues, this Pacific nation stands out as a linguistic marvel. While English holds the title of official language, only a small number of people speak it fluently. Instead, the majority rely on local languages and Pijin, a creole that bridges diverse communities.

This unique dynamic sets the Solomon Island apart from many other parts of the world. While most countries prioritize their official language, here, local dialects dominate daily life. For example, Pijin is spoken by over 90% of the population, making it the true lingua franca.

The linguistic landscape is further enriched by the presence of over 70 indigenous languages. This diversity reflects the cultural richness of the region. However, it also poses challenges, as many of these languages are endangered or at risk of disappearing.

To learn more about the languages of the Solomon Island, visit FamilySearch. For a broader perspective on the region’s cultural and linguistic diversity, check out Britannica.

Conclusion

The linguistic landscape of this Pacific nation reflects its rich history and cultural diversity. Over the years, events and policies have shaped its unique blend of languages. Pijin, the lingua franca, connects communities, while indigenous tongues preserve local heritage.

Influences from neighboring regions like Papua New Guinea add to this complexity. For example, Tok Pisin, a creole similar to Pijin, is widely used there. These connections highlight the shared linguistic roots across Melanesia.

At the province level, dialects vary, showcasing the region’s vibrant identity. Efforts to document endangered languages ensure their survival for future generations. Explore more about this fascinating topic on Wikipedia or the CIA Factbook.

The above is subject to change.

Check back often to TRAVEL.COM for the latest travel tips and deals.

0 Comments